APPLICATION OF PRENATAL TESTING FOR

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS. AN ILLUSTRATIVE CASE REPORT

Yapijakis C1,2, Serefoglou Z1, Sakellariou M1, Karahalios S3, Koufaliotis N3

*Corresponding Author: Christos Yapijakis, DMD, MS, PhD, Department of Neurology, University of Athens Medical School, Eginition Hospital, 74 Vas. Sofias, Athens 11528, Greece; Tel: +30-210-8811 243; Fax: +30-210-7289 125; E-mail: cyapijakis_ua_gr@yahoo.com

page: 67

|

|

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case Report: Diagnosis of a Congenital Syndrome. A Greek couple and their 4-year-old boy with congenital cleft lip and palate, came to our Center for diagnosis and genetic counseling for a probable following pregnancy. The boy was born with right cleft of the upper lip, cleft palate and a dysplastic right nostril, and had been submitted in a series of restorative surgical operations (Fig. 1). The rest of his medical history was free of any other serious condition, and he had a normal mental and physical development. The family history did not reveal any similar cases in four generations. The parents were unrelated as they originate from different regions of Greece. The boy’s clinical picture included a midface defect with hypertelorism, a broad nasal bridge and signs of restored dysplastic right nostril, cleft lip and palate, as well as only one upper central incisor (Figs. 2 and 3). The mother mentioned that during the second month of pregnancy she took estrogens, prescribed by the attending obstetrician, because of hemorrhage.

The clinical picture of the boy and his medical and family history suggested the diagnosis of frontonasal dysplasia (FND) of mild type A [17]. FND is a sporadic syndrome with midface defects, caused by several environmental factors, including the estrogens which are known to be associated with clefts [17-20]. The diagnosis of FND and its good prognosis for the child were communicated to his parents. The couple was also advised that no prenatal testing for frontonasal dysplasia was necessary in future pregnancies, provided that no estrogens would be taken during those periods.

Case Report: Prenatal Testing for CMV Infection. A year later, the same couple returned to our Center for genetic counseling because the attending obstetrician had advised them that the fetus being carried in a second pregnancy was probably infected by CMV. Already in the 19th week of pregnancy, the woman had been tested for serum anti-CMV antibodies at regular intervals and had been repeatedly found to be IgG positive and IgM negative. Nevertheless, she was advised by the caring obstetrician to have a molecular prenatal test following amniocentesis. Although not necessary, amniocentesis was performed at 18.5 weeks of pregnancy, and the PCR test indicated the presence of CMV DNA. The obstetrician advised termination of the pregnancy, and the distressed couple came to us in order to obtain a second opinion and for genetic counseling.

During a counseling session, in addition to psychological support, we discussed with the couple that the obtained data by others (IgG +, IgM -, and positive PCR prenatal testing) could raise two distinct possibilities: a) either there was an acute recurrence of CMV infection, thus although IgM were still negative a couple of weeks ago the embryo was at great risk of being infected; b) or there was no recurrence of CMV infection, and the PCR results were false positive due to a possible contamination of the amniotic fluid sample by maternal leukocytes, because of a rupture of a blood vessel during amniocentesis.

In order to distinguish between these two different options, and to better determine the risk to the fetus, the pregnant woman was advised to have a repeat test of serum IgG, IgM antibodies, and PCR detection of CMV DNA in her total blood and serum.

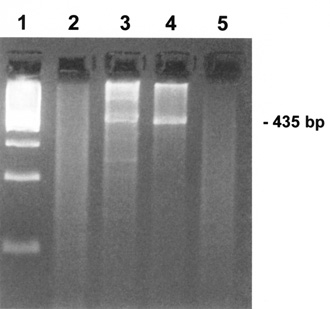

Methods. The anti-CMV IgG and IgM were qualitatively and quantitatively tested by standard ELISA methodology [13]. Total DNA was isolated by blood and serum of the woman using Nucleospin® Blood QuickPure Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Duren, Germany). Amplification of a 435 bp region of the Major Immediate Early gene of CMV was effected in a standard Taq DNA polymerase reaction of 50 mL, by using 5 mL DNA, primers MIE-4B (5’-CCA AGC GGC CTC TGA TAA CCA AGC C-3’), MIE-5 (5’-CAG CAC CAT CCT CCT CTT CCT CTG G-3’), and PCR conditions as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, 40 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min, 72°C for 3 min, and a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 min. In addition to the woman’s samples, the same PCR reaction was performed on a DNA sample from a CMV carrier (positive control) and a DNA sample of a non carrier (negative control). The PCR products were electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel in parallel with a molecular weight marker. The same molecular procedure was performed in two independent sets of reactions.

Figure 2. A 4-year-old child with midface defect signs: hypertelorism, broad nasal bridge, and restored dysplastic right nostril, and cleft lip/palate (frontonasal dysplasia).

Figure 3. A 4-year-old child with only one upper central incisor (frontonasal dysplasia).

Figure 4. Agarose electrophoresis of PCR products corresponding to a 435 bp fragment of the MIE gene of CMV. Lane 1: molecular weight marker; lane 2: serum sample of pregnant woman; lane 3: blood sample of pregnant woman; lane 4: positive control for CMV (DNA of a CMV carrier); lane 5: negative control for CMV (DNA of a non-carrier for CMV). The molecular test appears to detect CMV in the woman’s blood sample but not in her serum.

|

|

|

|

|

Number 27

VOL. 27 (2), 2024 |

Number 27

VOL. 27 (1), 2024 |

Number 26

Number 26 VOL. 26(2), 2023 All in one |

Number 26

VOL. 26(2), 2023 |

Number 26

VOL. 26, 2023 Supplement |

Number 26

VOL. 26(1), 2023 |

Number 25

VOL. 25(2), 2022 |

Number 25

VOL. 25 (1), 2022 |

Number 24

VOL. 24(2), 2021 |

Number 24

VOL. 24(1), 2021 |

Number 23

VOL. 23(2), 2020 |

Number 22

VOL. 22(2), 2019 |

Number 22

VOL. 22(1), 2019 |

Number 22

VOL. 22, 2019 Supplement |

Number 21

VOL. 21(2), 2018 |

Number 21

VOL. 21 (1), 2018 |

Number 21

VOL. 21, 2018 Supplement |

Number 20

VOL. 20 (2), 2017 |

Number 20

VOL. 20 (1), 2017 |

Number 19

VOL. 19 (2), 2016 |

Number 19

VOL. 19 (1), 2016 |

Number 18

VOL. 18 (2), 2015 |

Number 18

VOL. 18 (1), 2015 |

Number 17

VOL. 17 (2), 2014 |

Number 17

VOL. 17 (1), 2014 |

Number 16

VOL. 16 (2), 2013 |

Number 16

VOL. 16 (1), 2013 |

Number 15

VOL. 15 (2), 2012 |

Number 15

VOL. 15, 2012 Supplement |

Number 15

Vol. 15 (1), 2012 |

Number 14

14 - Vol. 14 (2), 2011 |

Number 14

The 9th Balkan Congress of Medical Genetics |

Number 14

14 - Vol. 14 (1), 2011 |

Number 13

Vol. 13 (2), 2010 |

Number 13

Vol.13 (1), 2010 |

Number 12

Vol.12 (2), 2009 |

Number 12

Vol.12 (1), 2009 |

Number 11

Vol.11 (2),2008 |

Number 11

Vol.11 (1),2008 |

Number 10

Vol.10 (2), 2007 |

Number 10

10 (1),2007 |

Number 9

1&2, 2006 |

Number 9

3&4, 2006 |

Number 8

1&2, 2005 |

Number 8

3&4, 2004 |

Number 7

1&2, 2004 |

Number 6

3&4, 2003 |

Number 6

1&2, 2003 |

Number 5

3&4, 2002 |

Number 5

1&2, 2002 |

Number 4

Vol.3 (4), 2000 |

Number 4

Vol.2 (4), 1999 |

Number 4

Vol.1 (4), 1998 |

Number 4

3&4, 2001 |

Number 4

1&2, 2001 |

Number 3

Vol.3 (3), 2000 |

Number 3

Vol.2 (3), 1999 |

Number 3

Vol.1 (3), 1998 |

Number 2

Vol.3(2), 2000 |

Number 2

Vol.1 (2), 1998 |

Number 2

Vol.2 (2), 1999 |

Number 1

Vol.3 (1), 2000 |

Number 1

Vol.2 (1), 1999 |

Number 1

Vol.1 (1), 1998 |

|

|